As SaaS companies face more competition and tighter margins, many are the traditional sales-led model with hybrid product-led growth. In this growth model, the product itself becomes the main driver of customer acquisition and retention. Product-led companies rely on real-time usage—not sales outreach—to prove value and build loyalty.

This article breaks down what product-led growth means for SaaS businesses and what makes it effective. You’ll learn about the benefits, the key metrics to track, how to put a PLG strategy into action, and what to watch out for during implementation.

Understanding product-led growth

Product-led growth (PLG) is a strategy where the product itself is the main way a company attracts, converts, and retains customers. Instead of relying heavily on a sales team, PLG puts the product front and center by letting users see its value firsthand and decide to keep using it based on their experience. This approach contrasts with sales-led growth, where sales teams play a major role in guiding potential customers through the process.

A key characteristic of product-led companies is the focus on self-service onboarding, allowing users to start using the product independently. The customer journey prioritizes product experience over traditional sales outreach, making it a compelling strategy for companies looking to scale. This shift in focus has made the product-led growth vs sales-led growth conversation increasingly relevant for SaaS companies aiming to stay competitive.

Product-led growth vs. sales-led growth

In product-led growth, the product itself is the main driver of customer acquisition, letting users try out the product and engage with it on their own terms. With self-service features like onboarding walkthroughs and freemium models, the goal is to make the product so appealing that it attracts users without heavy sales involvement.

Sales-led growth, in contrast, relies on salespeople to reach out to prospects and guide them through the purchasing process. While product-led growth is focused on using the product’s value to drive expansion, sales-led growth emphasizes personalized interactions.

Some SaaS companies may opt for a hybrid model, incorporating both strategies to better address the needs of different customer segments. Understanding the nuances of the sales-led approach can help companies decide which strategy to prioritize.

A recent report from Gainsight and RevopsSquared found that 58% of SaaS businesses already had a PLG model in place, and 91% were planning to increase their PLG investments.

Benefits of PLG for SaaS companies

By emphasizing the product’s value early in the customer journey, users can discover it on their own, allowing SaaS companies to scale more naturally. Some key benefits of product-led growth include:

Lower customer acquisition costs (CAC)

Product-led growth helps reduce customer acquisition costs by making the product itself the best sales tool. When users can try the product on their own through free trials, there’s less need for big sales teams early in the sales cycle. Instead of heavy outreach, companies can guide users through a self-serve experience. This keeps acquisition costs low and makes it easier to attract new customers at scale. Many companies today build entire onboarding processes around easy trial experiences and signups, letting users explore features before ever talking to a customer success manager or support team member.

Higher retention and expansion

When a company leads with a strong product experience, users stay longer. A self-serve, user-driven onboarding process helps customers get quick wins early on. Over time, the trust built through the product turns into expansion opportunities like upsell offers and add-ons. A good user experience leads to higher retention because users feel confident in the product’s value. In turn, this improves customer lifetime value. For example, a SaaS company might notice that customers who complete a key setup task within the first week are more likely to buy a premium plan later.

Faster go-to-market cycles through automation

Automation supports product-led growth by helping SaaS teams move quickly from development to launch. It takes care of repetitive dev tasks like testing, deployment, and code reviews, so engineers can spend more time building. Once a product is ready, automation speeds up release steps and reduces delays. After launch, it helps users get started right away through self-serve demos and guided onboarding. With fewer manual steps and faster feedback loops, teams can ship updates more often. This speed gives SaaS companies an edge in markets where timing matters.

Stronger product-market fit signals

In a product-led model, SaaS companies can track user actions in real time. Product analytics show where users find value, where they struggle, and which features drive engagement. Watching real behavior gives better product-market fit signals than surveys alone. Teams can shape new features around actual user needs instead of guessing. For example, if data shows most users drop off during onboarding, it’s a sign to simplify the process right away. Clear product analytics shorten the time it takes to align the product with the market.

Better user feedback loops

PLG speeds up feedback by connecting directly with users through the product itself with the help of in-app surveys and usage data. Instead of waiting for sales teams to collect feedback, product managers can watch how users interact and make changes fast. This tight feedback loop helps teams stay in tune with customer needs and improve the product’s value faster. Tracking the onboarding process with in-app actions keeps teams focused on what actually matters to users, not just what they say.

Increased virality and referral potential

One of the biggest hidden strengths of PLG is how it fuels virality. When products include built-in sharing features like invites or collaboration tools, they spread naturally through word-of-mouth. As more users invite others to join or use the product together, organic growth picks up speed. This creates a steady flow of new customers without the high costs linked to traditional marketing efforts. Strong referral systems make it easier to grow while keeping customer acquisition costs under control.

Scalable revenue growth

User-led growth supports natural scaling without putting pressure on sales teams. As users discover more value, they are more likely to upgrade plans and explore add-ons on their own. A strong product experience combined with simple in-product upgrade paths can drive steady revenue growth. This means companies can grow without hiring huge sales teams at every stage. By focusing on improving the customer journey and building good referral loops, SaaS companies can create steady, scalable growth with less friction.

Companies that commit to a strong product-led growth SaaS strategy often see faster results because the product itself becomes the main driver of new customer wins and long-term loyalty.

Top 8 metrics to track in a PLG model

Tracking the right metrics helps SaaS companies understand user behavior and improve product-led efforts. Without clear benchmarks, it’s hard to know if the product is doing its job or if users are dropping off before they see value. Here are eight metrics that every PLG company should keep an eye on.

- Product-Qualified Leads (PQLs): Users who hit key actions inside the product, like completing setup or using core features, showing they are ready to buy. If PQL numbers are low, it usually means users aren’t reaching value moments soon enough.

- Activation Rate: The percentage of new users who complete an important first milestone, showing they see early value. Low activation often points to confusing onboarding or unclear product benefits.

- Time to Value (TTV): The time it takes users to get their first success with the product. A long TTV risks losing users before they see why the product matters, so onboarding flows should aim to shorten it.

- User Engagement: How often and how deeply users interact with features over time. Weak engagement signals that users may not be finding ongoing value or could be at risk of churn.

- Retention Rate: The share of users who stick around past key periods like 30, 60, or 90 days. Falling retention rates often mean the product’s core experience needs to be stronger or more aligned to user needs.

- Conversion Rate (Free to Paid): The percentage of free users who upgrade to paid plans after using the product. If conversion rates stall, companies may need to highlight premium features better or rethink their pricing model.

- Expansion Revenue: Revenue earned from existing users upgrading or expanding usage. Strong expansion means users are finding deeper value without extra sales pressure, while weak expansion may show missed growth opportunities.

- Churn Rate: The percentage of users who cancel or stop using the product. High churn often points to weak onboarding or product gaps that need faster fixes.

SaaS reporting tools can be utilized to help teams track these metrics in real time, spot patterns early, and adjust before small problems turn into big ones.

How to implement a product-led growth strategy in your SaaS business

A well-planned PLG motion builds momentum by allowing users to experience value and make buying decisions independently. Here are key steps to take to implement a product-led growth strategy in your SaaS business:

Define clear goals

Start by setting goals tied to how you expect the product to perform. Focus on measurable outcomes like increasing product-qualified leads (PQLs), lowering customer acquisition costs (CAC), or improving activation rates. These KPIs help track progress and give every team—from product to sales—a clear picture of what success looks like. Without this kind of clarity, it’s easy to lose focus or misread user behavior. For example, if your goal is to grow PQLs by 20% in the next quarter, the product team knows that enhancing the onboarding experience and creating impactful in-app value moments are important to achieving that goal.

Build a self-serve onboarding experience

An effective onboarding experience should help new users find value fast, without needing hand-holding. Start with simple self-serve flows that guide users step-by-step. Use in-app guides and timed prompts to walk them through core actions. Break the experience into clear milestones like importing data, completing a task, or inviting a teammate, and track each one as a signal of activation. Optimizing onboarding this way cuts down on churn and shortens time to value. If users don’t reach that early “aha” moment on their own, the rest of your product-led strategy will struggle.

Choose the right pricing and freemium model

Your monetization model should support your PLG strategy, not get in the way of it. Freemium, tiered, and usage-based plans can all work, depending on how your product delivers value. A well-structured SaaS freemium model gives users early access to core features, then nudges them to upgrade when they hit usage limits, need premium tools, or add more team members. Running A/B tests and tracking time to value (TTV) across plans helps teams improve conversion and spot where users stall.

Align product, customer success, and sales teams

For a product-led growth strategy to work, every team needs to act on the same user signals. Product teams, customer success teams, and sales teams should share access to activation milestones and PQLs. When a user reaches a clear value moment, customer success can step in with support, and sales reps can follow up with personalized outreach. This alignment keeps the user experience consistent and helps each team focus on the right accounts at the right time, without relying on guesswork or gut feel.

Use product analytics to guide decisions

Product usage data gives teams a real-time view into what users are doing and where they’re finding value. Instead of relying on assumptions or anecdotal feedback, product teams can use product analytics to decide what to build, fix, or promote next. This data helps prioritize updates that improve activation or boost conversions. It also supports smarter messaging and onboarding tweaks. Tying roadmap decisions to real behavior keeps your PLG strategy grounded in the actual user journey—not just what teams think users want.

Considerations when building a PLG SaaS product

Designing a product-led growth approach takes more than tweaking onboarding or adding a free trial. Whether you’re starting fresh or shifting from a sales-led model, there are key parts of the product and company structure that need to line up. Getting these right early on makes the PLG strategy more sustainable and easier to scale.

Aligning teams around the PLG strategy

Leadership plays a key role in making product-led growth work. Everyone from product management to sales should be aligned not just on metrics, but on the company’s market strategy and how the product fits into it. Setting clear KPIs like activation rate or PQL volume gives teams something concrete to rally around. Holding regular syncs and using shared dashboards helps keep everyone aligned, especially when multiple teams are touching the user experience. When the product team, GTM leads, and sales all have visibility into what’s working, decisions move faster and efforts stay connected.

Balancing self-serve onboarding and sales-led engagement

Most successful SaaS products blend product-led and sales-led touchpoints. A good onboarding experience lets users explore on their own, but that doesn’t mean the sales team disappears. Sales should engage when there’s a clear signal, such as reaching a PQL threshold or showing interest in enterprise features. This balance is especially important during transitions from sales-led models, where it’s easy to overcorrect. Startups adjusting their approach can benefit from these best practices for adding a product-led motion to sales-led SaaS, especially when figuring out how and when to involve sales without disrupting the flow.

Measuring the right success metrics

In a product-led growth strategy, success isn’t just about how many people sign up or how much revenue shows up each month. What matters more is what happens after the signup. Metrics like conversion and retention rates show whether users are getting value from the product. Teams that stay focused on these signals—rather than surface-level numbers—build stronger products and make better decisions. The goal is to understand real user behavior so you can optimize the customer journey.

Reducing early-stage churn

Early churn often comes down to a weak first experience. A smoother onboarding process can fix this by guiding users toward key activation milestones. Tutorials and early prompts help move users forward in the first few days, which is when most users decide whether to stick around. Benchmarks vary, but aiming for a strong activation rate in week one is a good place to start. It also helps to track early usage signals that suggest someone might drop off. If a user isn’t engaging, the product team can flag a sales rep to step in with a personalized walkthrough or quick demo before the trial ends. Improving this part of the journey doesn’t just reduce churn. It also leads to a better overall customer experience.

Examples of successful PLG SaaS companies

Some of the most well-known names in B2B SaaS built their success on product-led growth. These companies didn’t rely on big sales teams in the early stages—they focused on delivering real value fast, making it easy for end-users to adopt, and letting word-of-mouth do the rest.

Calendly

Calendly is a standout example of how a clean interface and a single, useful feature can power huge growth. The product makes it easy to book meetings without back-and-forth emails. Its self-service model lets users sign up, connect their calendars, and start sharing booking links in minutes. That setup made it perfect for viral adoption—every invite sent introduced someone new to the product. This natural referral loop helped Calendly grow its user base quickly without needing a traditional sales engine.

Slack

Slack built its user base by solving common communication pain points with a tool that was easy to try, easy to use, and hard to give up. With a freemium model and self-serve signups, teams could get started without asking for budget or IT approval. Once inside, the product encouraged collaboration through team invites and shared channels. Each new message and notification made the product more useful and harder to leave.

Dropbox

Dropbox’s early growth was fueled by smart referral tactics and a seamless sharing experience. Users who referred others earned extra storage, which made inviting friends feel rewarding instead of forced. Combine that with a clean UX and instant file syncing, and the product became something people talked about and shared naturally. The freemium model gave users plenty of space to get started, and the smooth experience kept them coming back.

Zoom

Zoom grew fast by making video calls simple to join and easy to trust. Users didn’t need an account to hop on a call—just a link. The product’s speed and reliable performance helped it spread across teams and industries. It wasn’t just the tech that made it work; it was the low-friction setup that removed blockers and encouraged quick adoption. These choices made Zoom a go-to platform for both casual users and enterprise teams.

Atlassian

Atlassian scaled by letting users explore tools like Jira and Confluence on their own. Instead of building a large sales team, it focused on strong documentation and helpful in-product guidance. Teams could onboard themselves and get real value before ever speaking to a rep. This approach proved that even complex products can follow a product-led model when the experience is well designed.

Each of these companies built momentum through the product itself. Their self-serve experiences, user-focused design, and referral or sharing features gave them a growth engine that didn’t depend on constant sales outreach.

Scale your PLG SaaS with Maxio

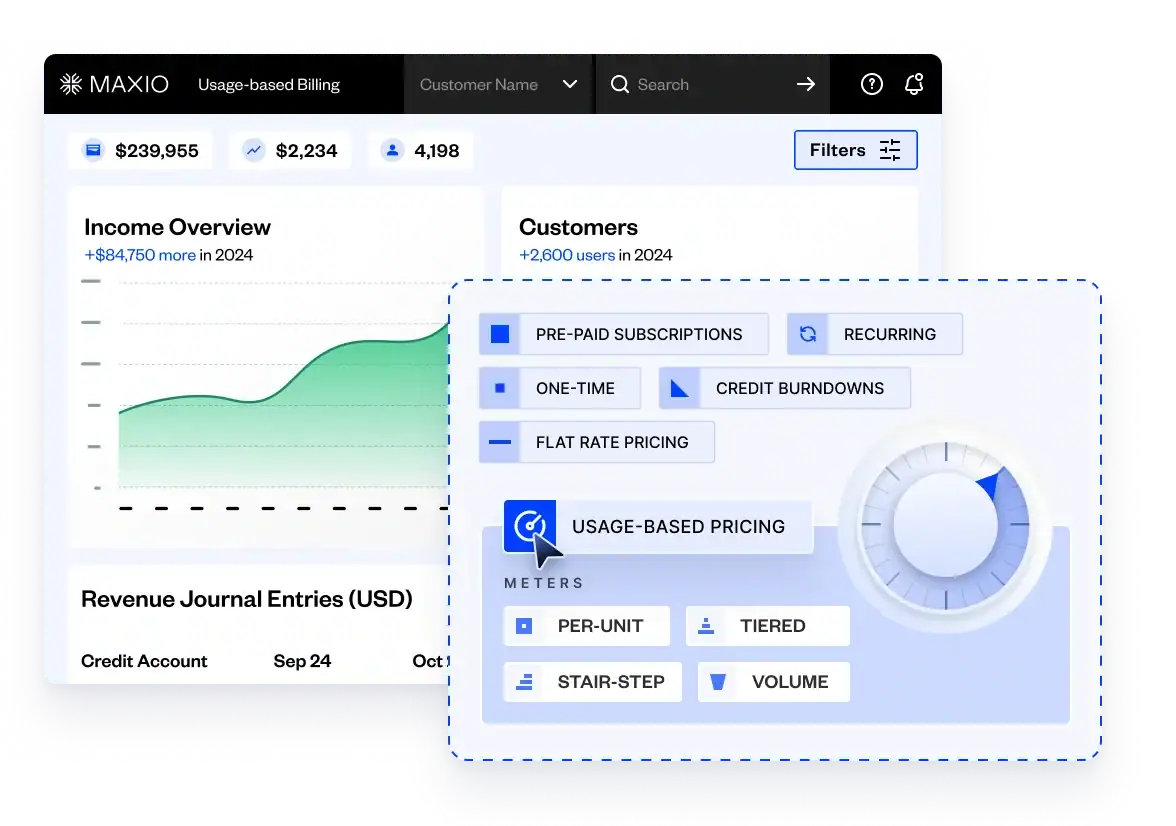

Product-led growth works best when SaaS companies can clearly see where users are finding value and how their actions tie into revenue. Maxio gives teams the data they need to track essential metrics to adjust strategy based on real behavior. Its product analytics and segmentation tools make it easier to see what’s working and where users drop off, so teams can focus their efforts where it matters.

Monetization is also easier to manage with Maxio. SaaS companies can test pricing, support usage-based models, and adjust billing without disrupting the customer experience. These changes can be tracked and easily refined over time, helping your company move faster without losing visibility.

Get a demo to see how Maxio supports every part of your PLG strategy—from activation to long-term revenue growth.